A New mRNA Vaccine Could Help Us Fight All Cancers and It’s Closer Than You Think

Scientists at the University of Florida have taken a bold step toward something medicine has long dreamed of a cancer vaccine that could work against many types of tumors, not just one. Unlike personalized treatments tailored to a single person’s cancer, this new mRNA vaccine is designed to be used widely, giving more people faster access to life-saving care.

TECHNOLOGYIN BRIEF

Thinkbrief

7/19/20253 min read

The early results, published this month in Nature Biomedical Engineering, come from mouse studies. But what they show is remarkable. The vaccine worked not just in one kind of cancer but in several, including skin, brain and bone tumors. Even better, when it was combined with existing treatments like checkpoint inhibitors, the results were dramatically improved.

So how does it work?

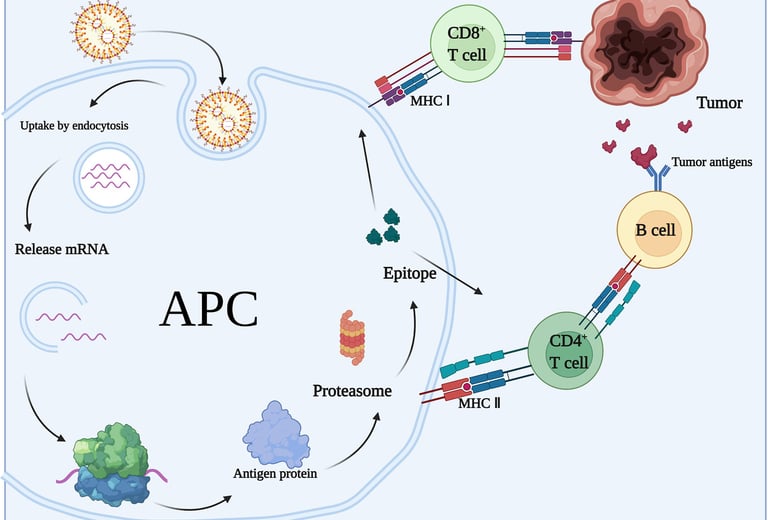

Instead of hunting down a tumor’s specific genetic makeup, which can take time, money and high-tech equipment, this vaccine takes a broader approach. It tricks the body into thinking it's fighting a virus. That may sound odd, but it’s a clever way to wake up the immune system. Once activated, the immune cells are on high alert and begin attacking cancer cells that might otherwise fly under the radar.

Dr. Elias Sayour, the pediatric oncologist leading the research, explained that this method essentially rewires the tumor environment. In plain terms, the vaccine helps expose the cancer so that the immune system can recognize it as dangerous and do what it does best, fight it.

This method is not meant to replace personalized vaccines, which are showing promise in trials from companies like Moderna and BioNTech. Those custom-made treatments teach the immune system to recognize the unique mutations in an individual’s tumor. But they also take weeks or months to produce and are not available to everyone.

The University of Florida’s approach, by contrast, is fast and general. That means it could be rolled out more easily in hospitals around the world, including in places where personalized medicine is not yet practical.

For patients and their families, this could change everything. Imagine being diagnosed with cancer and, instead of waiting for a treatment designed just for you, your doctor has a vaccine ready to go, one that could make your existing therapy work better or help your immune system fight the disease more directly. It is a future that feels closer now than it did just a few months ago.

Still, there is a long road ahead. What works in mice does not always work in people. The human immune system is more complicated, and cancer can be unpredictable. Researchers are now preparing for early clinical trials to test the vaccine's safety in people. They will also need to refine the formula, figure out the best way to deliver it, and determine which patients it helps the most.

There are also challenges beyond the lab. In the United States, debates over science funding, including support for mRNA research, have created uncertainty about how quickly this kind of work can move forward. But internationally, enthusiasm for cancer vaccines remains strong. The success of mRNA technology during the COVID-19 pandemic opened new doors for scientists, and cancer researchers have walked through them with purpose.

We are still at the beginning. But this vaccine, even in its early stages, gives hope. It shows that we might not need to wait for individualized, expensive treatments to help more people. We might be able to build something universal, a vaccine that strengthens the immune system and gives it the tools to see cancer for what it really is, an enemy that needs to be fought head on.

For families living with cancer, this kind of progress is more than just promising science. It is a sign that help could be on the horizon. A treatment that is not limited by genetics or geography. A vaccine that could be available at your local hospital, not just at elite research centers. And maybe one day, a world where we do not just treat cancer, we prevent it from taking hold in the first place.

We are not there yet. But this study shows we are getting closer.

And that, for millions of people hoping for a breakthrough, means everything.